Moles are small mammals that spend most of their lives in underground burrows. They are seldom seen by humans. When seen, they frequently are mistaken for mice or shrews. The eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus) is the only species that lives in Missouri and is found throughout the state (Figure 1).

The most conspicuous features of the mole are its greatly enlarged, paddlelike forefeet and prominent toenails, which enable it to “swim” through the soil. Moles have strong legs, short necks and elongated heads. They lack external ears, and their eyes are so small that at first glance they appear to be missing.

A mole’s fur is soft and brownish to grayish with silver highlights. When brushed, the fur offers no resistance in either direction, enabling the mole to travel either backward or forward within burrows.

Moles prefer moist, sandy loam soils in lawns, gardens, pastures and woodlands. They generally avoid heavy, dry clay soils. They construct extensive underground passageways — shallow surface tunnels for spring, summer and fall use; deep, permanent tunnels for winter use. Their nest cavities are located underground, connecting with the deep tunnels.

Moles have high energy requirements and thus have large appetites. They can eat 70 to 80 percent of their weight daily. They actively feed day and night at all times of the year. Moles feed on mature insects, snail larvae, spiders, small vertebrates, earthworms and, occasionally, small amounts of vegetation. Earthworms and white grubs are preferred foods.

Mole activity in lawns or fields usually appears as ridges of upheaved soil. The ridges are created where the runways are constructed as the animals move about foraging for food. Burrowing activity occurs year-round but peaks during warm, wet months. Some of these tunnels are used as travel lanes and may be abandoned immediately after being dug. Mounds of soil called molehills may be brought to the surface of the ground as moles dig deep, permanent tunnels and nest cavities.

Moles breed in late winter or spring and have a gestation period of four to six weeks. Single annual litters of two to five young are born in March, April or May. Young mole are born hairless and helpless, but growth and development occur rapidly. About four weeks after birth, the moles leave the nest and fend for themselves.

Moles in the natural environment cause little damage. They are seldom noticed until their tunneling activity becomes apparent in lawns, gardens, golf courses, pastures or other grass and turf areas.

Moles often are more of a nuisance than a financial liability. The ridges of their tunnels make lawn mowing difficult. Since the roots are disturbed, grass may turn brown and unsightly (Figure 2). Moles rarely eat flower bulbs, ornamentals or other vegetative material while tunneling, but plants may be physically disturbed as moles tunnel in search of animal organisms in the soil. Mole activity may indirectly damage vegetation, but their feeding on insects and other soil organisms is beneficial.

Shrews and meadow voles frequently use mole tunnels as runways and travel lanes. Shrews, like moles, are insectivorous and eat little vegetation. Meadow voles eat a wide variety of vegetative matter and may damage plant life. Moles, shrews and meadow voles can be similar in appearance. Because they look similar and often share the same habitat, you should know how their habits differ so you can identify each species in case it becomes necessary to control them.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Eastern mole.

Figure 2

Moles "swim" through soil, often near the ground surface. They may sometimes damage plants by exposing roots to drying.

Mole activity

The evidence of mole activity people usually see is raised ridges, or surface tunnels, and mounds. The raised ridges, or surface tunnels, are unique to moles. No other animal leaves this evidence of its presence, although mole activity often is confused with that of the pocket gopher, which also is found in Missouri.

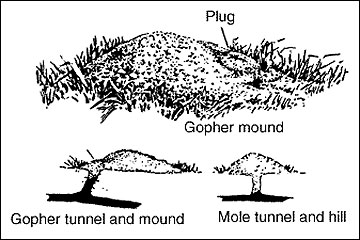

The cone-shaped mounds moles leave on the surface of the ground, often called molehills, most often contain coarse soil and earth clods. Moles do not usually build numerous mounds. Mounds are constructed as a mole digs a deep run and pushes soil up through the center, much as a volcano is formed (Figure 3). These deep runs lead to a nest or provide tunnels for use in the winter or during the hot times of the summer.

People often confuse pocket gopher mounds with mole mounds (Figure 4). The pocket gopher, however, does not construct raised ridges or surface tunnels. Pocket gophers dig two kinds of tunnels — one about 5 to 8 inches under the surface and other deeper tunnels that may go down several feet below the surface.

Unlike the mole, the pocket gopher constructs many mounds of finely sifted soil. Pocket gopher mounds sometimes can be rather large but most often contain about a half gallon of soil. The pocket gopher digs a main tunnel, then a lateral side tunnel to create the mound, where it deposits soil accumulated in digging the underground tunnels.

Pocket gophers are rodents and have different feeding habits than moles. Traps designed to catch moles usually will not catch pocket gophers, and vice versa. Therefore, correctly identifying which animal caused damage is important. Both animals may be present in some areas.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Moles push dirt through vertical tunnels onto the surface. Mounds are good places to use fumigants, since they are believed to mark deep runs or nest areas.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Comparison of a gopher mound and a mole hill.

Damage prevention and control techniques

The mole seems to possess a natural shrewdness and ability to sense danger, which makes trapping them a challenge. Other practices for ridding an area of moles include making the area less habitable and using repellents.

Cultural methods and habitat modification

In practice, packing the soil with a roller or reducing soil moisture may make an area less habitable for moles. Because moles feed largely on insects and worms, the use of certain insecticides to control these organisms may reduce the moles’ food supply, causing them to leave the area. Before leaving, however, the moles may increase their digging in search of food, thereby possibly increasing damage to turf or garden areas.

White grubs are a food source for moles, although even a grub-free lawn may have moles if other food sources are present. In the absence of other food sources, controlling grubs may eliminate moles. White grubs overwinter as larvae and move closer to the soil surface in the spring to pupate. White grubs found in spring are not a concern and applying insecticides at that time to kill the grubs and larvae of other soil insects is not justified. Mid-June to mid-July is the ideal window for insecticide applications targeting only white grubs. Insecticides applied earlier in the season to control other insects, such as billbugs, may effectively control white grubs but do not always work well. When insecticides are applied earlier than mid-June, lawn care services and homeowners need to closely monitor lawns for white grubs in August.

Contact your MU Extension center for recommendations for insect control in lawns. Always follow all precautions and restrictions on the pesticide label.

Repellents

The repellent Thiram is federally registered for protecting bulbs from mole damage. Mole repellents with castor oil as the active ingredient may prevent eastern mole damage under certain circumstances. When using any repellent, follow directions and application rates provided on the package label. Also, be aware that any repellent for controlling moles has limitations and may not eliminate damage or effectively control the problem.

Toxicants

Reliance on toxic baits to control nuisance moles is questionnable. Many toxic baits deliver their toxicant via grain, seeds or nuts, foods moles do not normally eat.

Baits with other delivery methods are also available. Toxic bait gels containing warfarin, such as Kaput Mole Gel Bait and Moletox Baited Gel, are injected into runways using a syringe applicator. Worm-shaped baits that use bromethalin as an active ingredient to poison moles, including Talpirid, Motomco Mole Killer and Tomcat Mole Killer, are dropped into runways and tunnels.

Although toxic baits offer an alternative approach for dealing with mole problems, little research has been done to determine whether they are a cost-effective alternative to other control recommendations, such as trapping.

Fumigants

Fumigants or gas cartridges registered for use in controlling moles are available, but they are are not generally recommended, as the tunnel systems are too long and often too porous for gas to be effective.

Traps

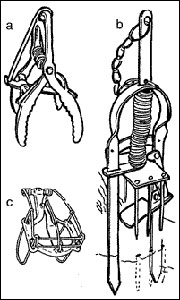

Although trapping is challenging, it is the most successful and practical method to get rid of moles and eliminate damage. Three excellent mole traps are on the market. All of them, if properly handled, will give good results.

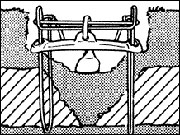

Each of these three mole traps depends on the same mechanism for releasing the spring. A broad trigger-pan springs the trap as the mole upheaves the depressed portion of the surface burrow over which the trap is set. The brand names of these traps are Harpoon mole trap, Out O’ Sight and Nash (choker loop) mole trap (Figure 5).

The Harpoon trap has sharp spikes that impale the mole when driven into the ground by the spring. The Out O’ Sight trap has scissorlike jaws that close firmly across the runway, one pair on each side of the trigger-pan. The Nash trap has a choker loop that tightens around the mole’s body.

These traps are well-suited to moles because they take advantage of the mole’s natural habits. The mole springs the traps by following its instinct to reopen obstructed passageways. Another advantage of these traps is that they can be set without arousing the animal’s suspicion because you do not have to enter or put anything into the burrow.

The success of these traps depends largely on the operator’s knowledge of the mole’s habits (Figures 6 and 7) and the trap mechanism.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Different mole traps available include

- Out O'Sight

(scissor-jawed) - Harpoon

- Nash

(choker loop)

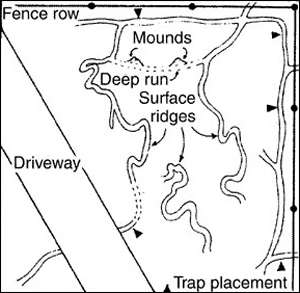

Figure 6

Figure 6

A network of mole runways in a yard. The arrows indicate good locations to set traps. Avoid the twisting surface ridges and do not place traps on top of mounds. Figure 7

Figure 7

A mole hill and ridge caused by tunneling of mole under sod arev signs of the presence of moles.

Setting a trap

Always be careful when handling a trap. Follow these basic steps to set a trap properly:

- Select a place in the surface runway where fresh work is evident and the burrow runs in a straight line.

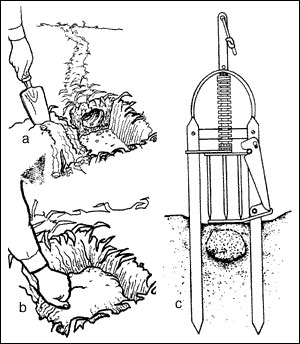

- To place the trap, dig out a portion of the burrow, locate the tunnel and replace the soil, packing it firmly beneath where the trigger-pan of the trap will rest (Figures 8a and 8b). Follow the instructions below for setting the specific type of trap you are using.

- Set the trigger on all mole traps with a hair trigger.

- Release the safety hook.

Figure 8

Figure 8

- Excavating a mole tunnel is the first step in setting a trap.

- Replace the soil loosely in the excavation.

- The harpoon-type trap is set directly over the runway so that its supporting stakes straddle it and its spikes go into it when tripped.

Harpoon trap

To set a Harpoon trap, raise the spring, set the safety catch and push the supporting spikes into the ground, one on each side of the runway (Figure 8c). The trigger-pan should just touch the earth where the soil is packed down. Once the trap is in place, release the safety catch. Do not step on or otherwise disturb any other portion of the mole’s runway.

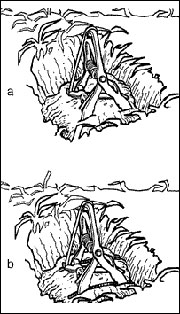

Scissor-jawed trap

To set a scissor-jawed trap, dig out a portion of a straight surface runway and repack it with fine soil. Set the trap, and then secure it with a safety hook with its jaws forced into the ground about an inch below the runway. The trap should straddle the runway (Figure 9a) until the trigger-pan touches the packed soil between the jaws.

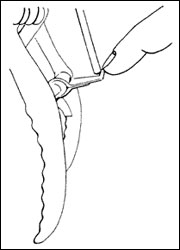

Check that the trap is in line with the runway so the mole will have to pass directly between the jaws. In heavy clay soils, cut a path for the jaws (Figure 9b) so they can close quickly. The jaws of this trap are rather short, so be sure the soil on the top of the mole runway is low enough to bring the trap down nearer to the burrow. Set the trigger with a hair trigger as shown in Figure 10.

To set a choker trap, digging a hole across the tunnel is usually necessary. Make the hole a little deeper than the tunnel and just the width of the trap (Figure 8b). A garden trowel is useful for digging this hole. Note the exact direction of the tunnel from the open ends and place the set trap so that its loop encircles this course (Figure 11). Block the excavated section with loose, damp soil from which all gravel and debris have been removed. Pack the soil firmly underneath the trigger-pan with your fingers and settle the trap so that the trigger rests on the built-up soil. Finally, fill the trap hole with enough loose dirt to cover the trap level with the trigger-pan and to exclude all light from the mole burrow.

If a trap fails to produce after two days, move it to a new location. Trap failure can occur for several reasons:

- The mole changed its habits and is no longer using the runway.

- The runway was disturbed too much.

- The trap was improperly set and the mole detected it.

Figure 9

Figure 9

- The scissor-jawed trap is set so that the jaws straddle the runway.

- In heavy soils, make a path for the jaws to travel so they can close quickly.

Figure 10

Figure 10

Regardless of the type of mole trap used, set the trigger so it will spring easily. A hair trigger setting on the scissor-jawed trap is shown here.

Figure 11

Figure 11

The choker loop trap is set so that the loop encircles the mole's runway.

Catching moles alive

Moles can be caught at work early in the morning or evening where fresh burrowing operations have been noted. Approach very quietly where the earth is being heaved up. Strike a spade into the ridge behind the animal and throw the animal out onto the surface.

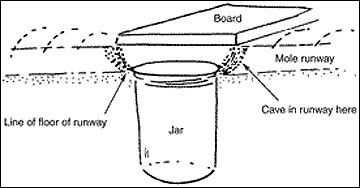

You may be able to drive a mole to the surface by pouring a stream of water from a hose or ditch into an open burrow for some time. Another live-capture method is to bury a three-pound coffee can or a wide-mouth quart glass jar in the path of the mole and cover the top of the burrow with a board (Figure 12).

Captured animals can be released in other areas of your property where their activity will not be objectionable.

Figure 12

Figure 12

in a pit trap. Be sure to use a board or other object to shut out all light. Cave in the runway just in front of the jar on both sides.

Other methods

Nearly everyone has heard of home remedy for controlling animals, especially moles. These remedies recommend many and varied materials for placement within the burrow system. In theory, these materials cause the mole to die or at least leave, but in practice, this is not the case.

Suggested materials have included broken bottles, ground glass, razor blades, thorny rose branches, bleaches, various petroleum products, sheep dip, household lye and even human hair. Others include mole wheels, pop bottles, windmills, bleach bottles with wind vents placed on sticks, and other similar gadgets, which although colorful and sometimes decorative, are not effective mole control methods.

Other home remedies are the so-called mole plant, or caper spurge (Euphorbia lathris), and the castor bean. Advertisers claim that when planted frequently throughout the lawn and flower beds, such plants act as living mole repellents. No known research supports this claim.

Several electromagnetic devices or “repellers” have been marketed for the control of rats, mice, gophers, moles, ants, termites and various other pests. The claimed effects on rodents include stopped feeding and reproduction, disorientation, and dormancy or death by dehydration. These same devices reportedly have no harmful effects on domestic livestock, cats, dogs, bees, earthworms or other “useful” animals and insects. Scientific testing has not confirmed any of these claims.

Unfortunately, there are no short cuts or magic wands for controlling moles. Some garden experts, frustrated by lack of knowledge about trapping, recommend inserting chewing gum in mole burrows, another home remedy that has not been proven effective.

Economics of damage and control

For commercial agricultural producers, elimination of moles over large areas is difficult, if not impossible. For the homeowner, problems with moles usually can be managed with minimal effort and persistence. Because of the mole’s solitary habit and rather low productivity, most residential yards can be maintained mole-free for a number of years.

Before initiating a control program, be sure the mole you are after is truly out of place. Moles play an important role in the management of soil and of grubs that destroy lawns.

One of the most abundant small mammals, the mole works the soil and subsoil. This tunneling and shifting of soil particles permits better aeration of the soil and subsoil, carrying humus farther down and bringing the subsoil nearer the surface where the elements of plant food may be made available.

In addition, a large percentage the mole’s diet is made up of white grubs, which are insect pests of turf grasses and plant roots. Stomach analyses have revealed that nearly two-thirds of the moles studied had eaten white grubs, with one mole having eaten as many as 175. They also eat the larvae and adults of numerous other insect pests, such as Japanese beetles, that affect garden, landscape and flowering plants.

If an individual mole is not out of place, consider it an asset and proceed accordingly. If you do have moles where you don’t want them, remove them. But if excellent habitat is present and nearby mole populations are large, control will be difficult. Often other moles will move into areas that have become vacant.

Additional information

- Fresenberg, B. and T. Teuton. Managing lawns and turfgrass (MG10). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Extension.

- Godfrey, G., and P. Crowcroft. 1960. The life of the mole. London: London Museum Press.

- Henderson, F. R. 1994. “Moles.” In Prevention and control of wildlife damage, edited by S. E. Hygnstrom, R. M. Timm, and G. E. Larson, D-51 to D-58. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension.

- Henderson, F.R. 1990. Controlling nuisance moles (C-701). Manhattan, KS: Cooperative Extension Service.